*Content Warning: This piece contains subject matters such as depression, suicide, and substance abuse.

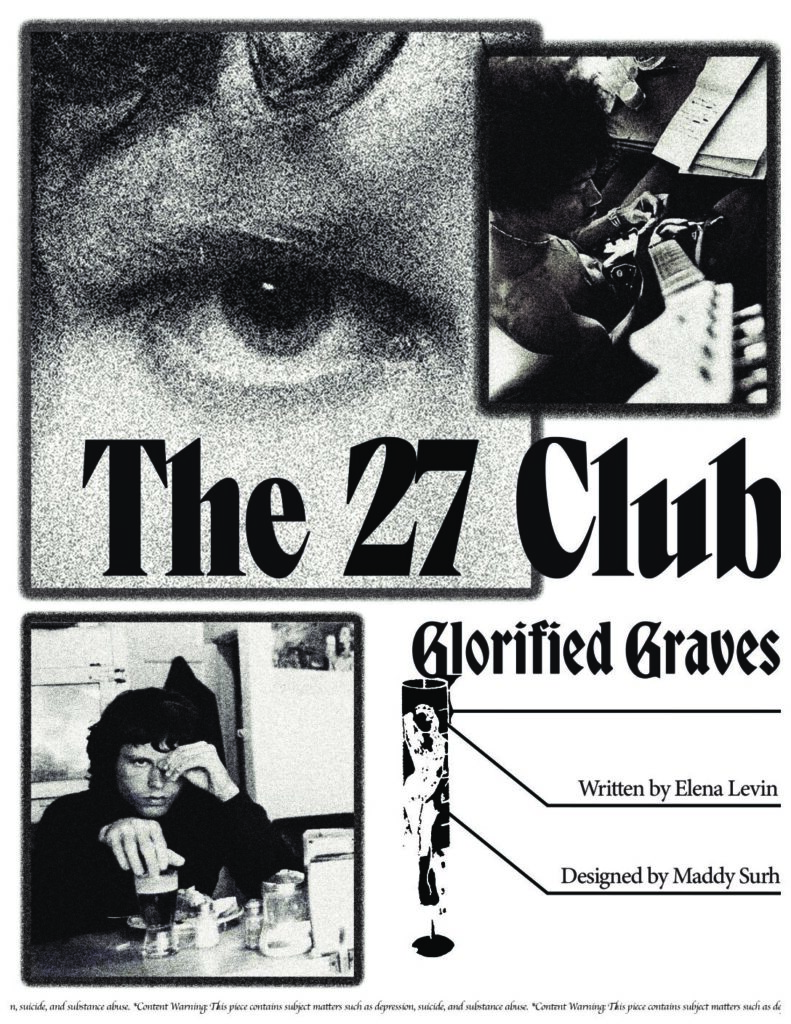

Sex, drugs, and rock and roll seem like the recipe for the “perfect” life, but for some, it’s a recipe for disaster. 27, on its surface, is an arbitrary number–– but not within the music world. Artists across decades have been eerily linked together on the basis of their age at death, with many clinging to the comforting thought that they’re all hanging out together in “Rock and Roll Heaven.” When most people think of the infamous “27 Club,” there are typically six major musicians that come to mind: Brian Jones, Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison, Janis Joplin, Kurt Cobain, and Amy Winehouse. Spanning between the years of 1969 and 2011, the lives of these “big six” were taken by the devastating consequences of substance abuse and mental illness, highlighting the mental health crisis within the music industry.

Design by Maddy Surh

Thinking back to the days of childhood naïveté, nearly everyone at some point dreamt of becoming a rockstar–– I know I did. Yet within this fantasy is a blatant ignorance of what really comes with stardom; the long nights in the studio, grueling months and years of tour disrupting one’s routine, constantly being surrounded by drugs and alcohol, and the sudden commodification that accompanies being in the public eye. While some may rejoice at these prospects of fame, the pressure that these musicians face is incomprehensible to those who have yet to experience it. Sadly, that is why many of our greatest talents have turned to substances as a vice for coping with a life in the limelight .

Society has crafted a glamorized narrative of rock-stardom, with phrases such as “live fast, die young,” or “I’m here for a good time, not a long time,” permeating pop culture. Thus, when there is someone in the music industry that’s struggling, we’ve learned to turn a blind eye time and time again. The problem lies in assumption–– How could they possibly be unhappy when they have everything that I want? But perhaps that’s the very root of it. Since many of these artists struggled with mental illness and self esteem before their rise to success, once they reach the point of “rock and roll utopia,” all the focus is placed on their mental state. In other words, if they were unhappy before, they are now solely faced with the weight of their dissatisfaction with life, due to the elimination of the more “mundane” daily worries.

Sadly enough, for many of the members of the “27 Club,” their discography echoes their discontent with the world and their lives, reflected in some of the last songs they wrote before their death. One of the most explicit examples of this can be seen in the lyrics of Nirvana’s “You Know You’re Right.” The song opens with the lines: “I will never bother you/ I will never promise to… Never speak a word again/ I will crawl away for good,” which, in context of Cobain’s suicide months after the song’s recording, reads as a kind of declaration from the singer.

Within the track you hear Cobain’s sultry eruptions of raw emotion and defeat as he repeats “I always knew it would come to this/ Things have never been so swell/ I have never failed to fail” in the lead-up to each chorus.

Another heartbreaking example can be seen in the unreleased “Like a Long Time (No Tomorrow)” written by Ronald “Pigpen” McKernan, one of the founding members of The Grateful Dead. Starting the song off he speaks of the feeling of being watched by “ten thousand people,” but how he feels he is no different than anyone else. He then goes on to state “Seems like there’s no tomorrow/Seems like all my yesterdays were filled with pain/There’s nothing but darkness tomorrow,” and “Don’t make me live in this pain no longer/You know I’m getting weaker not stronger,” which can be seen as explicit expressions of depression or other mental illness.

Chris Bell, one of the leaders of Big Star, spent his last years writing I Am the Cosmos (1992), a solo album released posthumously. Throughout the album, Bell’s melancholy melodies are peppered with lyrics addressing his depression including “It’s suicide/I know, I tried it twice” in “Better Save Yourself,” and “Spending all my time/Waiting to die/What’s the use” in “There Was a Light.” Like many of the members of the “27 club,” it is unknown whether or not the tragic car accident that took Bell’s life was executed with intent, especially when considering the fact that he had a history of suicide attempts. The line between planned and accidental becomes increasingly blurred within the countless overdoses among “the 27s.” Who’s to know if Hendrix or Alan Wilson intended to take a lethal dose of barbiturates, or if Jones had some sort of resolve when he dove into his swimming pool? Or were Joplin, Kristen Pfaff, and Jeremy Michael Ward simply unlucky with their heroin dosage that fateful night?

Design by Maddy Surh

One of the more chilling stories of the “27 Club” accompanies the death of Mia Zapata, the lead singer of the Seattle-based punk band, The Gits. As the band geared up for their second album, Zapata was brutally raped and strangled to death in July of 1993. Unsettlingly enough, a week earlier the band had recorded “The Sign of the Crab,” written by Zapata, that featured the lyrics “Go ahead and slice me up, spread me all across this town/’Cause you know you’re the one that won’t be found.” Strangely prophetic, the disappointing truth is that Zapata’s death has been paralleled in the lives of countless women, and her song intended to shed light on that injustice. Yet, little did she know she would be a part of a case of male brutality that remained unsolved until 10 years after her death.

As other stars neared their own end, some turned to the comfort of religion. Pete Ham, the lead vocalist of Badfinger, seems to take solace in God as seen in “Ringside”–– a track from his posthumous album Misunderstood (2023). Amidst acoustic guitar, Ham’s soulful voice pleads, “Take me back to the father/Take me, take me, take me home,” mere months before he hanged himself in his garage. Similarly, Hendrix’s “The Story of Life” is coated with biblical imagery, such as the crucifixion of Jesus, ultimately resulting in the resolution: “The story of life is quicker than the wink of an eye/The story of love is hello and goodbye/Until we meet again.” Written down and dedicated to his girlfriend at the time, Monika Dannemann, these lyrics were considered a kind of suicide note by Hendrix’s friend Eric Burdon when found among his personal belongings.

However, although the “27 Club” shines a spotlight on some of the world’s most notable musicians, it is exclusive in nature. Unfortunately there are countless casualties in the music industry, and not all of them happen at the age of 27. Therefore there are an abundance of musicians that aren’t given the same attention or “standing” due to the fact that their premature deaths were off by a couple of years. Some of these equally devastating losses include Otis Redding at 26, Jeff Buckley at 30, Mac Miller at 26, and Tupac Shakur at 25, to name a few.

The real question at hand is: What is being done to combat the mental health crisis in the music industry? According to a 2019 study by Record Union, 73% of independent musicians struggle with their mental health, with 80% of those individuals being between ages 18 and 25. Another study conducted in 2018 by Music Industry Research reported that the percentage of musicians with depression is double the percentage of the general population, with 12% reporting suicidal thoughts. Clearly, there is an issue here. The beginnings of reform came in 1989 with the establishment of MusiCares, an organization for providing medical and financial assistance to musicians. Other efforts specifically related to mental health have come about more recently, including: Music Support, Music Minds Matter, and Backline. Each of these organizations are dedicated to connecting individuals in the music industry to professional clinical and therapeutic services, with some even operating a 24/7 phone hotline. At the end of the day it is crucial to recognize that behind each great artist is great pain; “It’s not just sex, drugs, and rock & roll anymore. It’s how sex, drugs, and rock & roll can have a long-term impact,” expressed Backline’s clinical director Zack Borer.

Needless to say, too many of the music greats have fallen victim to the throes of mental illness and substance abuse, a significant number losing their lives to that fight at the age of 27. Yet, in place of these tragic losses lies a lasting legacy. Stated best by Morrison in what is believed to be the last song he wrote, “Riders on the Storm”: “Our life will never end.” It’s true their lives will never end, but their artistic lives were unfortunately cut short, robbing the public of decades of music.

Written by Elena Levin, Design by Maddy Surh